Table of Contents

- The future of immigrant children is the future of the nation.

- Environments, institutions, family conditions and resources around children affect their health and potential.

- Anti-immigrant conditions are social determinants of health with wide-ranging negative consequences on child development, including children who are U.S. citizens.

- Precarious legal status has wide-ranging negative effects on children of immigrants.

- Fear of parental deportation hurts the development of children of immigrant families, hinders life achievement, and could prove costly to society.

- The trauma resulting from forced family separation also happens in neighborhoods throughout the U.S. and far from the border.

- The new public charge rule will have a chilling effect on child development and health.

- Improve the social determinants of health to improve life outcomes for children of immigrant families.

- About the authors.

- Full report.

- References.

https://www.fcd-us.org/determinants-of-health-and-well-being-for-children-of-immigrants/

In Determinants of Health and Well-Being for Children of Immigrants: Moving From Evidence to Action, Dr. Lisseth Rojas-Flores and Jennifer Medina Vaughn summarize ground-breaking research, funded by the Foundation for Child Development’s Young Scholars Program (YSP), which illustrates the dire situation of children of immigrants in the U.S. today. The authors use a social determinants of health framework to illuminate how social, economic, and sociopolitical conditions directly influence a child’s overall well-being as well as their physical and mental health. Anti-immigrant environments and policies create a climate of fear and foster adverse mental health due to trauma and potential physical deprivation that all lead to poor child development and life-long outcomes. Click here to read the full report.

The future of immigrant children is the future of the nation.

The United States is a country of immigrants, with successive waves of immigrant families contributing to the social and economic growth of the nation. As our nation’s population ages, children under the age of 18 who reside with at least one foreign-born parent are propelling the growth of our country’s childhood population — and its future workforce.

Environments, institutions, family conditions and resources around children affect their health and potential.

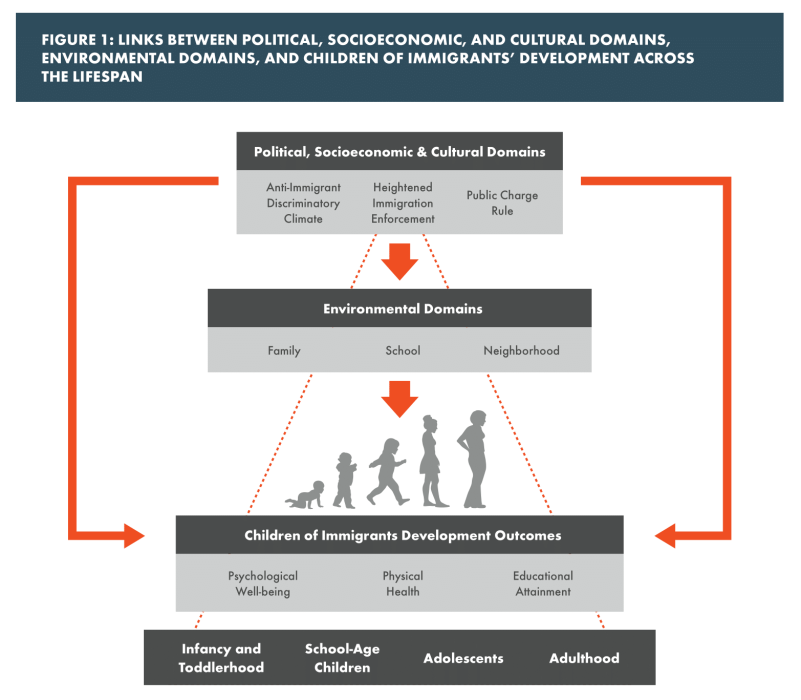

Social determinants of child health are the social, economic, and sociopolitical conditions that directly influence a child’s overall well-being, including the prevalence and severity of developmental problems. Children are dependent on their caregivers — family, schools, public institutions and community resources — for protection against the effects of socio-structural factors associated with disadvantage and social exclusion. The chart below shows how political, socio-economic and cultural policies directly shape the environments where children grow, play and learn, in turn impacting their psychological well-being, physical health and educational attainment from infancy through adulthood.

Today’s anti-immigrant climate, discriminatory social policies, and heightened immigration enforcement create and perpetuate unprecedented challenges for this growing young population, resulting in short- and long-term negative developmental outcomes that are costly for children and society. YSP scholars have provided evidence of the childhood vulnerabilities created by living within hostile environments. These include fear of public service officers,[1] disruptions to ethnic identity formation[2], and emotional distress.[3]

Precarious legal status has wide-ranging negative effects on children of immigrants.

Accumulating evidence indicates that our nation’s current sociopolitical climate and policies have widespread implications that extend to U.S. citizens — especially vulnerable children of immigrants — and have an impact on their development across the lifespan.[4] The precarious legal immigration status of a parent is a determinant of mental[5] and physical health[6] and appears to be related to poor academic achievement[7] for children and youth of immigrant ancestry.

Fear of parental deportation hurts the development of children of immigrant families, hinders life achievement, and could prove costly to society.

A survey of health care providers indicated that since the November 2016 elections, there has been an 87% increase in reports of anxiety and fear among children of immigrants associated with higher detention and deportation rates.[8] The uncertainty and unpredictability generated by policies supporting heightened immigration enforcement, compounded by anti-immigrant messages, seem related to anticipatory anxiety symptoms described by children of immigrants.[9] Anticipatory anxiety is debilitating and has been linked to anxiety disorders and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.[10] Anxiety symptoms are a costly public health issue associated with increased visits to primary care providers, medical specialty care providers, and emergency departments, as well as functional impairments, including school absenteeism, school refusal, and poor academic performance.[11] Childhood anxiety disorders also increase the likelihood of being diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder in adulthood[12], further increasing the public health burden.

The trauma resulting from forced family separation also happens in neighborhoods throughout the U.S. and far from the border.

Several YSP researchers have demonstrated that losing a parent to detention or deportation results in debilitating psychological distress and trauma symptoms,[13] hampers academic achievement,[14] diminishes children’s overall sense of self-efficacy and self-esteem[15] and reduces civic engagement.[16] Another unintended effect of parental detention and deportation on children of immigrants is increased foster care placement.

The new public charge rule will have a chilling effect on child development and health.

On October 15, 2019, a “public charge” policy change, which will impact immigrant eligibility for lawful permanent residency (LPR), a requirement for citizenship, will come into full effect. For the first time in U.S. history, the public charge rule now classifies immigrants who participate in health, nutrition and housing assistance programs as “burdens on American taxpayers,” making them ineligible for LPR status.[17] The “burden” is defined as accessing programs such as Medicaid, subsidized housing, and government supported nutrition programs (such as SNAP, or food stamps), among others. It is widely expected that the public charge rule will produce a chilling effect on utilization of vital safety net programs by an estimated 23 million immigrant families.[18] Those eligible will likely avoid enrolling themselves and their eligible citizen children so as to not jeopardize their citizenship, as well as out of confusion and distrust of federal agencies. This could lead to mass Medicaid disenrollment, greater food insecurity, and increased homelessness or substandard housing conditions for many children of immigrants, further aggravating their social determinants of health and future productivity. For the past several years, Young Scholars’ research has highlighted detrimental effects of lacking health insurance for immigrant pregnant mothers and their offspring,[19] and school-aged children.[20] Young Scholars’ work also provides evidence of negative impacts of food insecurity[21] and substandard and insecure housing[22] for children in low-income, immigrant families. YSP research strongly suggests that the new public charge rule will only exacerbate already existing child health disparities in our nation.

Based on extensive research by the Young Scholars, policymakers, communities and institutions are urged to pay special attention to improving the social determinants of the health of children of immigrants. Recommended strategies include:

- Moving toward inclusive policies for better child outcomes. Replace exclusionary policies that foster child health inequities towards inclusionary policies that take to heart the best interests of our young generation of children of immigrants.

- Promoting universal public safety net policies. Shift towards a universal public safety net and promote public policies that improve healthcare and housing access and offer funding for nutritional programs for all children — regardless of their ancestry or their parents’ legal immigration status.

- Protecting the health of children of immigrants by reducing disparities in state and local policies. Medical health coverage should be consistent (i.e., programs offered, income cutoffs, enrollment procedures, etc.) across the nation in order to reduce confusion, create consistency, and facilitate enrollment.

- Supporting immigrant parents and reducing stress in mixed-status families. As a nation that cares for its children, we must also support immigrant parents and mixed-status families who are experiencing heightened levels of stress associated with immigration enforcement and discriminatory climates. Curtailing caregiver stress can help protect children against the physical and mental health consequences of chronic and toxic stress that come from growing up in hostile environments.

- Supporting and training teachers and schools on how to support children of immigrant families. This includes empowering teachers to be multi-disciplinary mentors in the classroom, promoting inclusionary school strategies and policies, and investing in parent-school partnerships.

- Investing in neighborhoods and immigrant communities. Community contexts are social determinants of child health. Increased accessibility to center-based childcare, nutrition programs, community food centers, and after-school programs for children can provide opportunities for positive social interaction and physical activity that may counteract neighborhood risks and associated poor health outcomes.

Lisseth Rojas-Flores, Ph.D. is a former Young Scholar from 2012-2015. Dr. Rojas-Flores is an associate professor in Clinical Psychology at the Fuller Graduate School of Psychology in Pasadena, CA. Jennifer Medina Vaughn, M.S., is a doctoral candidate in Psychological Science at Fuller Graduate School of Psychology.

Full report.

Please click here to read the full report.

References.

[1] (Dreby, 2012; Rojas-Flores, 2017)

[2] (Ayón, 2015; Brown, 2015)

[3] (Ayón & Philbin, 2017; Brabeck et al., 2016; Rojas-Flores, et al., 2017)

[4] (Perreira & Pendroza, 2019; Rojas-Flores, 2017)

[5] (Hainmueller et al., 2017; Rojas-Flores, Clements, Hwang Koo & London, 2017)

[6] (Vargas & Ybarra, 2016)

[7] (Brabeck, et al., 2016)

[8] (Shore & Ayon, 2018)

[9] (Dreby, 2012; Rojas-Flores, 2017; Brabeck & Xu, 2010; Shore & Ayon, 2018)

[10] (PTSD; see Grillion et al., 2009)

[11] (Ramsawh, Chavira & Stein, 2010)

[12] (Pine, Cohen, Gurley, Brooke, & Ma, 1998)

[13] (Rojas-Flores, 2017; Rojas-Flores et al., 2017)

[14] (Mechure, Rojas-Flores & Clements, 2019;)

[15] (Ayón & Becerra, 2013; Bajaras-Gonzalez et al., 2018)

[16] (Nichols, Lebron, & Pedraza, 2016)

[17] (US Department of Homeland Security, 2018a)

[18] (Batlava, Fox & Greenberg, 2019)

[19] (Green, 2012; Kaushal & Kaestner, 2005)

[20] (Crosby & Hatfield, 2008)

[21] (Gee, 2018; Kimbro & Denney, 2015; Denney, Kimbro & Sharp, 2018; Potochnick, Perreira, et al., 2018)

[22] (Leventahl, Dupéré * Shuey, 2015)